For decades, child marriage in Assam was discussed in reports, debated in policy circles and condemned in public speeches. But on the ground, change often felt slow and uneven. Now, the latest figures suggest something different Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates, and the scale of decline is significant enough to demand serious attention.

According to state data, child marriages among girls below 18 have declined by 84 percent. Underage marriages below 21 years have reportedly fallen by 91 percent. Teenage pregnancies have dropped by 75 percent.

These are not marginal improvements. If sustained, they represent one of the most substantial social shifts in the state’s recent history.Child marriage is not just a legal violation. It reshapes the life of a girl permanently.

Early marriage almost always means interrupted education. It increases the likelihood of early pregnancy, maternal health complications and long-term economic dependency. In rural belts of Assam, where poverty and limited access to higher education intersect, the practice has historically been deeply entrenched.

So when officials state that Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates, the implications stretch far beyond compliance with law. It potentially signals change in social behavior.

The Enforcement Factor

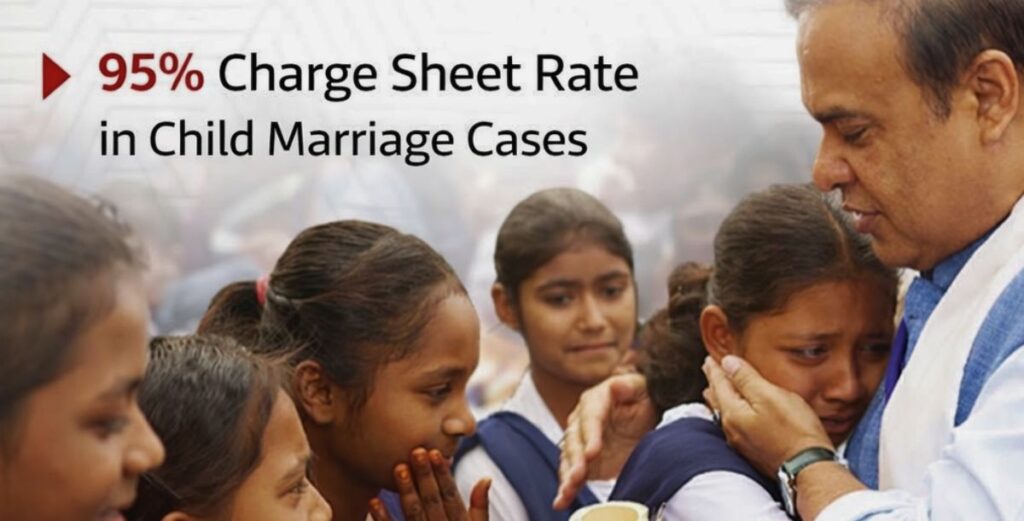

The recent crackdown gained momentum under Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma.

District administrations were instructed to act decisively. Thousands of cases were registered under child protection laws. Authorities report a 95 percent charge sheet filing rate unusually high for social crime categories.Legal deterrence appears to have altered the risk calculus for families considering early marriage.

But enforcement alone rarely explains social change. It may trigger fear. It does not automatically transform belief systems.Interviews with educators and field-level health workers indicate a layered approach.

Village awareness meetings explained legal age limits and medical risks of adolescent pregnancy. Anganwadi workers and ASHA health staff reportedly engaged directly with families identified as vulnerable.

Monitoring systems were strengthened. In some districts, local officials intervened before marriage ceremonies could take place.This combination visible legal consequences plus persistent awareness may explain why Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates rather than merely improved reporting.

The Health Dimension

A 75 percent decline in teenage pregnancies deserves equal focus.Adolescent pregnancy significantly increases risks of anemia, obstructed labor and neonatal complications. Public hospitals in rural Assam have long struggled with high-risk early pregnancies.

If teenage pregnancies are indeed declining at this scale, maternal and infant health outcomes could improve over time. That would reduce pressure on public health systems and improve intergenerational well-being.One of the most telling long-term metrics will be school retention.

When girls stay in school longer, marriage is naturally delayed. Secondary education completion strongly correlates with higher income potential and lower fertility rates.

If Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates consistently over several years, education statistics should reflect that shift.Policy analysts suggest that the true success of the campaign will be visible not in police data, but in classrooms.

Caution Before Celebration

While the percentage declines are striking, independent district-wise breakdowns are still awaited. Sustainable change must be measured across multiple years.Social reform is rarely linear. There can be temporary dips followed by rebounds if monitoring weakens.

Experts also point out that economic vulnerability remains a root driver. Without strengthening livelihood support and access to secondary education, enforcement gains may plateau.

India’s Prohibition of Child Marriage Act has existed for years. Yet enforcement varies widely across states.If Assam’s approach proves durable, it could offer a replicable model: combine legal seriousness with localized awareness and preventive monitoring.

However, the credibility of this shift will depend on transparent data, continued funding for girls’ education and consistent political will.For families in Assam, this moment carries practical consequences.

Delayed marriage means more time for education.

More education means better employment prospects.

Better employment prospects alter household economics.

When Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates, it is not merely a governance headline. It is potentially a generational reset.

The immediate question is sustainability.

Will enforcement remain strong once media attention fades?

Will awareness programs continue at village levels?

Will economic schemes support families so that marriage is not seen as financial relief?

Structural social change requires persistence.

Conclusion

The data suggests a remarkable shift: Assam sees sharp drop in child marriage rates, alongside a major decline in teenage pregnancies.But real success will be measured five and ten years from now in graduation rates, maternal health statistics and women’s workforce participation.

For now, Assam stands at a critical juncture. The numbers show progress. The challenge is turning that progress into permanence.